Part II: Understanding Soft Skills

Connecting with Your Inner Compass: Emotional Intelligence at Work

Years ago, I was working in a team facing a moment filled with uncertainties and changes in the workplace. We were in a team’s meeting. All of us were talking at the same time and flooding our leader with questions. Clearly overwhelmed, our team lead paused and said, “Please, give me five minutes. I will be right back.” When they returned, they had recollected themselves and calmly addressed the team:

“Sorry, that was too much at once. It made it difficult for me to make an informed decision. From now on, I would like the team to better prepare for these meetings and bring forward well-defined concerns that have been pre-discussed across the team. I want our meetings to be focused and streamlined so we can be productive, not overwhelmed.”

We listened and adjusted, faster than expected! We became more intentional in how we collaborated and prepared the meeting agenda. We set up pre-meetings, voted on topics, made decisions (when possible), discussed issues amongst ourselves and the senior leadership before bringing it up to our leader. It allowed us to connect with each other, solve conflicts and find ways to have a collective opinion, while reducing the burden on our leader and allowing them to focus on key issues that really required their attention.

When a leader or mentor owns their emotions, communicate honestly, and take responsibility, they demonstrate emotional intelligence. This moves the whole team forward. They become models on how to deal with uncertainty, tension, and general human complexity. Let’s dive into why that matters…

What is Emotional Intelligence?

“The language of the emotions, as it has sometimes been called, is certainly of importance for the welfare of mankind.”

- Charles Darwin, Evolutionist (The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals).

Just like many other animals, human beings have emotions. But what exactly is an emotion? Emotions can be defined as complex psychological and physiological responses that influence our thoughts and behaviors.

In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Charles Darwin explored the evolutionary origins and universality of emotional expressions by analyzing facial muscles and body changes related to emotions in man and animals. Interestingly, throughout his life, Darwin made detailed notes on his own children’s behaviors including when they began to cry after birth, when tears first appeared, and how they reacted to fear or being startled. He also observed domestic animals (like dogs and cats), and wild one (like monkeys), noting how they expressed joy, affection, fear, and other feelings.

While some of Darwin’s interpretations have been debated, his work laid some of the foundation for our modern understanding of emotions. Researchers like Frans de Waal have since explored emotions in the lives of animals in greater depth. In Mama’s Last Hug (2019), de Waal describes how non-human primates’ express emotions like joy, anger, fear, sadness, through facial expressions, body language, and vocalizations, remarkably similar to humans. Meanwhile, neuroscientists have identified key brain regions involved in emotional processing, such as the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

Together, this research suggests that emotions are not just random, learned or purely cultural. They are deeply rooted in our biology. They serve as powerful tools for communication, survival, and decision-making. So the next time you feel angry, sad, or afraid, try to notice and embrace these emotions without judgement. They are not a flaw, but a part of what makes us human.

What really matters is how we respond to these emotions. At the heart of emotional intelligence sits our awareness of them and our ability to manage the consequences. Emotions influence how we perceive the world, solve problems, engage in conflicts, and think creatively.

To understand this more intuitively, imagine a boat sailing smoothly on a sunny day. Suddenly, a storm approaches, dark clouds are on the horizon, and unpredictable winds strike the sails. Fear kicks in! Now the captain must process this emotion, take control, and guide the next steps. The crew, also frightened, must manage their own fear, stay alert, communicate clearly, and support each other. If panic takes over, chaos might follow, and the boat could sink.

This ability to manage and consciously respond to emotions is what psychologists Peter Salovey and John Mayer defined in 1990 as emotional intelligence:

“The ability to monitor one’s own and other’s emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use the information to guide one’s thinking and actions.”

Psychologist Daniel Goleman later expanded the term linking it to broader social competencies like leadership and empathy (check the next sections for more about his framework). Salovey and Mayer’s model includes four key components: (1)perceiving emotions, (2) using emotions to facilitate thought, (3) understanding emotions, and (4) managing emotions.

Other models have emerged as well. The Bar-On model blends emotional and social abilities, while the Petrides and Furnham model focuses on self-perceived emotional ability. For example, how we think we handle emotions and how that perception shapes our behavior.

Across studies, these frameworks have consistently shown that emotional intelligence is linked to stronger social relationships, academic performance, workplace success, and psychological well-being. It has come to be seen as a predictor of real-world success, distinct from, and perhaps as important as, general intelligence.

Components of Emotional Intelligence

“People will forget what you said... but they will never forget how you made them feel.”

- Maya Angelou, American memoirist, poet, and civil rights activist.

Understanding that life unfolds in unimaginable ways is essential not just for maintaining emotional stability, but also for supporting employee retention and well-being. Mentors and mentees alike need to be aware of their emotions, especially during times of change and uncertainty.

💡 Here are just a few examples: receiving a difficult health diagnosis, the sudden loss of a loved one, a car accident that leaves someone temporarily unable to work, a particularly hard day, or a miscommunication that derails a deadline. And of course, there are larger scale disruptions, like a global pandemic, that have triggered or intensified mental health challenges for many. The list is long, because life is unpredictable. It pushes us through rough waters and fast winds, often without warning.

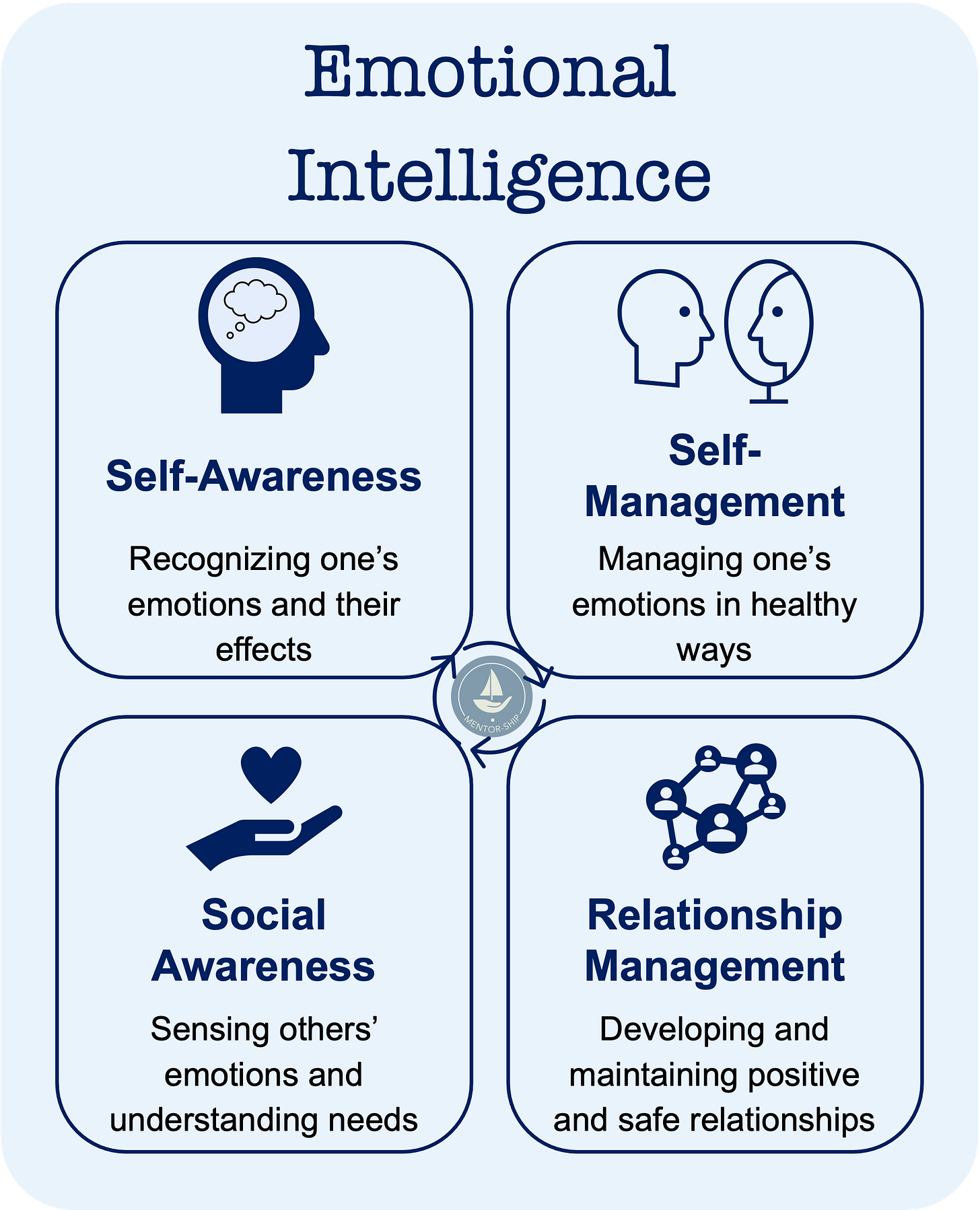

To better navigate those moments, we can turn to a widely used framework based on Daniel Goleman’s work, which breaks Emotional Intelligence into 4 interconnected competencies:

1. Self-Awareness:

Meaning: The ability to recognize and understand your own emotions, triggers and values, and how they influence your behavior. Imagine turning the flashlight inwards and observing yourself without judgment. It is about labeling and understanding your emotion.

Questions to ask yourself: What am I feeling right now? Why? What triggered this feeling? Are my values challenged or affirmed in this moment?

Mentorship: As mentors are often seen as leaders, self-awareness is essential. It involves recognizing personal biases, blind spots, and emotional reactions, especially under stress. A mentor who is self-aware can model reflection and create space for mentees to do the same, guiding them to articulate their own goals and concerns rather than imposing their own worldview.

2. Self-Management:

Meaning: the ability to regulate your emotions, adapt to change, remain calm under pressure, and maintain a positive outlook. It is about managing your responses rather than being ruled by them.

Questions to ask yourself: How often do I react impulsively and regret it later? Which strategies help me stay grounded when I feel overwhelmed? Do my moods dictate my behavior? How do I recharge emotionally after a difficult day/interaction?

Mentorship: Mentors composure and emotional regulation are a model for responses in challenging situations. Showing self-control of and filtering instincts creates a positive outlook that have the potential to be mirrored by the mentee. Mentors and mentees must recognize when to pause setting a standard for healthy emotional processing.

3. Social Awareness/Empathy:

Meaning: The ability to perceive and understand emotions, needs, and perspectives of others. This includes both empathy and awareness of group dynamics or organizational culture.

Questions to ask yourself: Do I notice body language, tone shifts, or nonverbal cues in conversations? Do I listen to understand, or just to reply? How do I react when someone’s experience challenges my own views? When someone shares a challenge, do I try to fix it or just be present?

Mentorship: Socially aware mentors are familiar to what mentees say, and what they don’t. They notice subtle shifts, offer space for honest conversation, and validate different perspectives. Their empathy fosters psychological safety, encouraging vulnerability, connection, and growth without fear of judgment.

4. Relationship Management:

Meaning: The ability to navigate interpersonal interactions with skill-building trust, resolving conflict, influencing positively, and supporting others’ development.

Questions to ask yourself: How do I handle conflict: avoid it, confront it, or resolve it? Am I willing to apologize and take responsibility when I commit a mistake? Am I approachable when people need help? How do I support others in difficult times?

Mentorship: Effective mentors are not afraid of tough conversations. They tend to embrace them with honesty and compassion, providing clear, constructive feedback and supporting mentees through conflict, and foster mutual respect. Through these interactions, they build resilient relationships that grow stronger over time.

Working on Emotional Intelligence Skills

“Emotional intelligence is learned and learnable at any point in life.”

- David Goleman, American psychologist, author, and science journalist.

Life circumstances challenge mentors and leaders to navigate emotional moments with adaptability and care. At the same time, employees and mentees often find themselves in emotionally charged situations that call for tact, empathy and thoughtful action. Feelings like sadness, anger, and anxiety are part of being human, but recognizing those emotions, processing them, and responding appropriately is a skill in itself.

These are interpersonal tools we all needed to live, work, and thrive in a community. Yet not everyone grows up in an environment that encourages emotional growth. Many people start their careers without access to inspiring leadership, structured mentorship, or even basic mental health support like behavioral therapy. Without these supports, it is difficult to move from instinctive reactions to intentional responses, and to build the emotional intelligence that helps us grow.

❓So, how can someone begin to work on their emotional intelligence?

Let’s steer the boat back and focus on strategies for each of the 4 core principles of Emotional Intelligence:

1. Self-awareness

Pause during the day: Take a short 5-10 minute break. Instead of picking up your phone to see the latest news, have a meeting with yourself. Ask: What am I feeling right now? Why? This simple practice, also called mindfulness, helps you notice your inner state. (Article)

Journaling: Grab a notepad and a pen! At the end of day, sit with yourself and write about triggered you, what lifted you up, and what drained you. This helps track emotional patterns. Just like any exercise, with time, you will begin to notice these patterns without thinking too much about them. (Find more information here)

360˚feedback: Be open to honest and constructive input from others. Ask your mentor or mentee for their insights about your performance, communication style, and how you handle difficult situations or confrontations. Feedback helps uncover blind spots and expands self-awareness. (More in this article)

2. Self-management

Use the pause: In the middle of a discussion or confrontation, pause! Take a breath and bring your focus back to yourself. In that moment, it is helpful to choose logic over reaction.

Imagine the following scenario: a piece of equipment breaks down, and people start pointing fingers at each other and to you. Emotions are high. Pause, breath, and think logically. Rather than reacting to the emotion, focus on the problem at hand: offer to troubleshoot, call the technician, ask to borrow someone else’s equipment (if that is an option), and suggest a short meeting to go over what might have gone wrong. This shows calm under pressure, logic over ego, and it helps build stronger, more respectful relationships.

Develop coping strategies: As mentioned above, pausing to breath is a great starting point. Other helpful strategies include taking a walk, listening to your favorite music (a way to ground yourself), or calling someone you care about to take your mind off the situation, even just for a minute. (Find ways to cope with stress in this article)

Reflect on your reactions: We are all human. You might lose your temper or react poorly from time to time. If it happens, take a moment later to reflect, or journal, about why you reacted that way and what you would want to do differently next time.

Build healthy habits: It is much harder to regulate emotions when you are exhausted, hungry, or not feeling well. Regular movement, activities that bring you joy, setting healthy boundaries, and prioritizing self-care will support emotion regulation over time.

3. Social awareness

Listen to understand: Mentees may come to you with a situation that triggered them emotionally. Instead of jumping in to fix it, ask questions that help them explore what they are feeling and why. Your perspective might be biased with your own upbringings, or you may not have the full picture. Talking things through in their own words, based on their backgrounds and previous experiences, helps them process better. This approach is similar to coaching. So, give them space to reflect while you offer guiding questions. (more on active listening in this Video)

Observe nonverbal cues: Words are powerful, but not everyone is comfortable expressing emotions directly. Pay attention to body language, awkward silences, or shifts in tone. Ask yourself: what am I missing here? Is there an emotion they might be feeling but not showing? For example: sometimes what looks like anger might actually be sadness or grief. Spotting those cues can help you better support your mentee. (Article on nonverbal cues)

Get curious but not judgmental: if someone is not acting like themselves, gently ask what might be going on. A mentor who is in tune with their team notices when something feels off. When you have created a positive and supportive environment, those check-ins become easier, and far more meaningful, than saying nothing at all.

4. Relationship management

Conflict Management: Avoid letting tension linger for days. When a conflict happens, follow up soon with an honest apology and an open conversation. Clearing the air quickly builds trust and often strengthens the relationship. Additionally, stay calm during tensions, identify a common ground and find ways to separate the real-life issue from emotions (Find more information in this Audio)

Be an inspirational leader: Remember to be consistent with your words and actions, and be clear on reasons why you might be acting or responding differently. Find ways to keep the team engaged and articulate purpose continuously (e.g. all-hands meeting with leadership sharing the current achievements and the focus for next year; reminding the goal of a project or of the mentorship). You can also model vulnerability. As even superheroes have weaknesses, why should mentors and leaders be any different? When a mentor openly shares how they are feeling or admits a fragile moment, it creates space for others to feel safe and do the same.

Practice appreciation: There is no need for grand gestures like award or galas. A simple thank you, a genuine compliment, or setting aside a few minutes to celebrate the end of a project can go a long way. These moments of appreciation boost morale and deepen emotional connection with your team or mentees. This is also a way to build bonds and create lasting and healthy relationships. Other ways to strengthen your team is following up on conversations, remembering details that matter to others, and being trustworthy and reliable.

As a final consideration, developing emotional intelligence skills helps us build tools for navigating the unpredictable. When challenges arise, the goal is never to isolate the mentee or to send them off on a life raft, hoping they will figure it out alone. A mentor with emotional intelligence can pause, assess the situation, engage in honest conversation, and offer the support and resources needed. Some of these tools can be paired with pre-established programs available by the organization, including sabbatical, short- and long-term leave (more developing leave programs in this Article), medical health resources, pairing with other types of mentors.

While we are getting our Mentor-Ship ready for its next route, we invite you to take a moment and reflect on your emotional intelligence.

💡Think of a moment when you were able to manage your instincts and respond with intention. What made it go right?

💡Now, think of a time when you reacted instead of responded. What triggered you? Why was a pause not enough or not possible? What would you do differently next time?

Hop aboard! Mentor-ship is charting the course for a brand new section. See you there…⛵️

💬 Share in the comments tools that help you improve your emotional intelligence.

⛵️Keep sailing with us! Subscribe so you don’t miss our next post…

🌊Feeling lost at sea? We’ve got your back. Message me using the link below or through my website